From Shetland to the Azores: a practical guide to Europe’s new spaceports

The North Atlantic at night can be silent – just wind and waves. On a remote Norwegian island, under a thin ribbon of aurora, engineers close the last panels on a launch tower. Europe no longer has a single “gateway to space.” Alongside the crucial European Spaceport in French Guiana (CSG), which we covered in a separate post, a mosaic of vertical launch sites is taking shape: different places, different specializations – together forming a network of routes to orbit.

This article is the first in a series where we look at Europe’s emerging spaceports from different angles. In future posts, we’ll come back to topics like regulation, funding models and how these sites might work together as a network.

Why more than one vertical port?

Europe is not replacing CSG with a single new site, but building a small network of specialised launch pads. Several factors push in that direction:

- Different headings to orbit. Northern sites naturally favour polar/SSO trajectories, while Atlantic-facing pads reduce overflight of populated land.

- Safety corridors and local regulation. Each location has its own airspace, shipping lanes, population density, and regulator; some trajectories or risk envelopes are only acceptable from specific sites.

- Redundancy and resilience. Multiple ports reduce the risk of a single point of failure from weather, technical issues, or political constraints at any one location.

- Throughput and launch cadence. More pads and operators increase the likelihood of aligning narrow launch windows and campaign timelines with customer needs.

- Room for private players. New commercial launch providers and infrastructure consortia need options; they are more likely to invest if they are not locked into a single site or owner.

- Local ecosystems and skills. Each spaceport anchors its own cluster of jobs, test ranges, and suppliers, which in turn strengthens Europe’s overall industrial base.

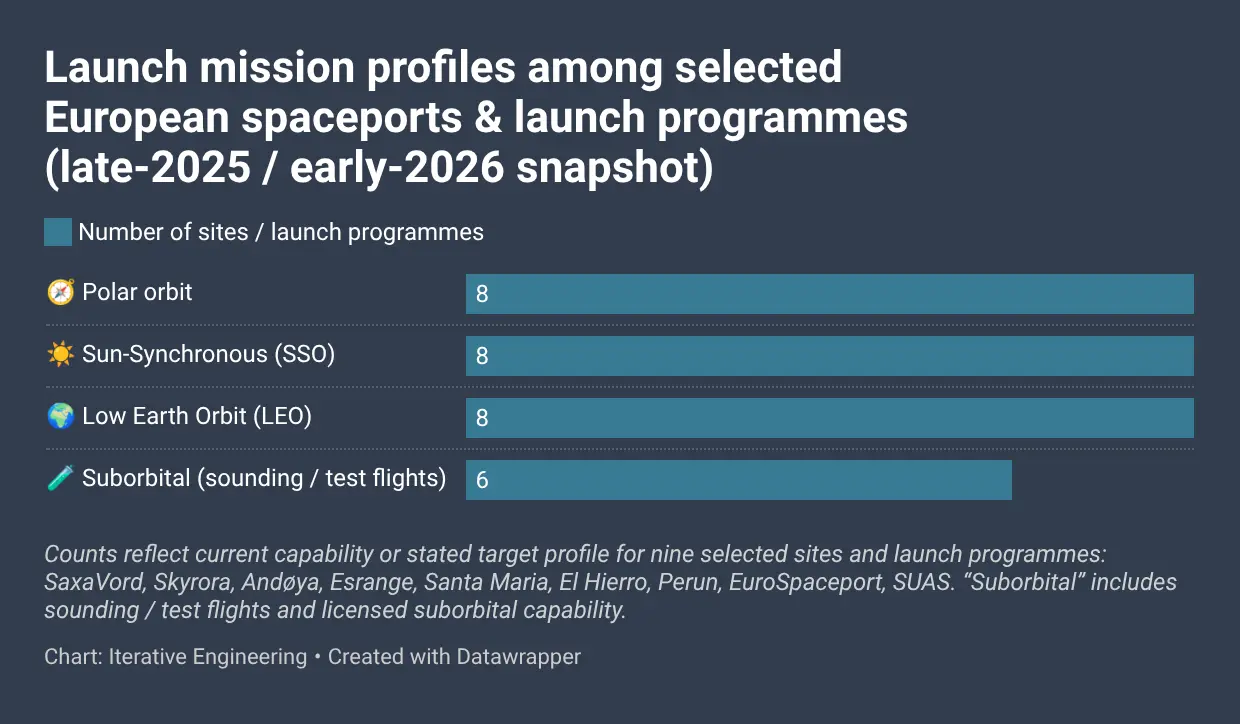

Europe’s launch landscape is still early-stage: multiple small spaceports and new microlaunchers are coming online, but real cadence is uncertain and not all will endure. As several speakers in Bremen put it, the bottleneck isn’t tech so much as maturity and regulation – we need licensing measured in months, not years, and repeatable processes that don’t restart from zero each campaign. Near-term demand will likely be anchored by dual-use and institutional missions, with commercial volume following as costs fall. Programmes like ESA’s Boost! and the European Launch Challenge help, but the market will ultimately pick winners. Interoperability and light-touch standards will matter – just not before first flights. Think less “one super-site,” more a network that can scale when real demand shows up.

Getting oriented in orbit: the essentials

SSO (Sun-Synchronous Orbit) – a type of high-inclination (often near-polar) LEO orbit designed so the satellite passes over a given area at roughly the same local solar time on each revisit. That consistency is ideal when you want repeatable lighting conditions (e.g., “always daytime” imaging) for Earth observation in environmental monitoring, agriculture, urban analytics, and security.

Polar orbit – a high-inclination orbit (near 90°) where the satellite travels roughly north–south, crossing over (or near) the poles as Earth rotates beneath it. Great for broad global coverage; not necessarily sun-synchronous unless specifically designed as SSO.

LEO (Low Earth Orbit) – the workhorse region for Earth observation, short-range telecom, and science/technology payloads (e.g., instrument tests, microgravity experiments). Many polar and SSO missions live here.

Suborbital – “up and back.” A ballistic flight that doesn’t complete an orbit; used for tech demos, short microgravity experiments, atmospheric research, and training.

Beyond the basics (common destinations for heavier launchers)

MEO (Medium Earth Orbit) – higher than LEO, lower than GEO; used for navigation constellations and some telecom/science missions.

GEO (Geostationary Orbit) – ~35,786 km altitude over the equator; satellites match Earth’s rotation and appear fixed over one longitude, making GEO a go-to for weather monitoring and broadcast/telecom.

Interplanetary / escape trajectories – transfers that leave Earth orbit towards the Moon, asteroids, or planets; these typically demand higher energy and often favor launch sites and vehicles optimised for heavier payloads.

Who excels at what – and where to click for more

SaxaVord (Shetland, UK) – Northern hub for vertical launches

Type: Spaceport (vertical; three launch pads at Lamba Ness).

Strength: Flight paths and risk zones mainly over ocean.

Status (incl. estimated cadence): Fully licensed by the UK Civil Aviation Authority to host up to 30 launches per year; infrastructure in place; first orbital campaigns expected ~2026. (Nov 2025): The first launch window has slipped to next year, according to local reporting, while licensing and infrastructure remain in place. Cadence: low at start (≈1–3/yr), potentially 5–10/yr once customers ramp.

Operator: SaxaVord Spaceport – privately operated launch site on Unst in the Shetland Islands, developed to host small-satellite missions from multiple launch providers using high-latitude trajectories over the North Atlantic. Key launchers: RFA One, Skyrora XL, HyImpulse SL1, ABL RS1, Latitude Zephyr.

Tidbit: “Edge of the UK” positioning reduces conflicts with shipping and aviation.

Official site: saxavord.com

SaxaVord Spaceport (UK) – RFA One three-stage launcher concept targeting up to 1,300 kg to a 500 km polar orbit

SaxaVord Spaceport (UK) – RFA One three-stage launcher concept targeting up to 1,300 kg to a 500 km polar orbit

Credit: Rocket Factory Augsburg • Licence: ESA Standard Licence

Andøya (Norway) – From mature suborbital base to orbital readiness

Type: Spaceport (vertical; legacy sounding-rocket range plus a new orbital launch pad).

Strength: decades of suborbital operations converted into robust orbital procedures; ocean-facing corridors.

Status (incl. estimated cadence): licensed spaceport with permission for up to 30 launches per year; first orbital test flight of Spectrum conducted in March 2025, ending prematurely but providing valuable flight data, with further campaigns in preparation; (Dec 2025): Isar Aerospace completed 30-second integrated static-fire tests on both Spectrum stages and is preparing its second launch from Andøya. Cadence: suborbital several/yr; orbital ~1–3/yr at start.

Operator: Andøya Space – an aerospace company based on Andøya Island in northern Norway with over 60 years of operations, providing launch and test services for scientific, commercial and governmental customers.

Tidbit: rare case of one site “graduating” from suborbital to orbital within the same campus.

Official site: andoyaspace.no

Vertical launch of a rocket from a pad

Vertical launch of a rocket from a pad

Photo: Isar Aerospace / Brady Kenniston – NASASpaceflight.com. Editorial use only; do not alter or remove copyright notices

Esrange (Kiruna, Sweden) – From research range to regular orbital missions

Type: Spaceport (vertical; sounding-rocket and balloon range with the LC-3 orbital launch complex).

Strength: EU’s largest rocket/balloon R&D backbone; new orbital pad.

Status (incl. estimated cadence): orbital launch complex operational (LC-3); first satellite launch campaigns contracted from 2026; no orbital launches conducted yet as of early 2026; (Nov 2025): Esrange conducted two sounding-rocket campaigns (MAPHEUS-16 and ORIGIN-2), underscoring sustained suborbital cadence ahead of orbital campaigns. Cadence: suborbital several/yr; orbital ~1–3/yr at start.

Operator: SSC (Swedish Space Corporation) – over 50 years in space services, operating Esrange and a global commercial ground station network for satellite communications.

Tidbit: polar night and harsh climate are a reliability proving ground during R&D.

Official site: sscspace.com (Esrange / Launch Services)

Satellite launch infrastructure under construction at Esrange Space Center, Kiruna, Sweden

Satellite launch infrastructure under construction at Esrange Space Center, Kiruna, Sweden

Image: SSC Space / Esrange Space Center. Courtesy of DLR GSOC. Editorial use only

Santa Maria (Azores, Portugal) – An Atlantic pad in deployment

Type: Spaceport (vertical; Malbusca Launch Centre on Santa Maria Island).

Strength: corridors over open ocean; minimal overflight of populated land.

Status (incl. estimated cadence): first Portuguese spaceport licence granted in 2025 for the Malbusca Launch Centre; infrastructure being deployed, with initial launches targeted from spring 2026. Cadence after commissioning: ~1–3/yr to begin with. (Nov 2025): Portugal and ESA signed a cooperation agreement positioning Santa Maria as the future landing site for Space Rider and consolidating the island’s space hub development.

Operator: Atlantic Spaceport Consortium (ASC) – Portuguese consortium developing an open spaceport on Santa Maria Island, licensed in 2025 to operate the Malbusca Launch Centre and provide launch and re-entry services from the mid-Atlantic.

Tidbit: the island already supports comms and tracking; launch operations to follow when works conclude.

Official site: spaceport.pt

Santa Maria station (Azores, Portugal) – part of ESA’s ESTRACK ground station network

Santa Maria station (Azores, Portugal) – part of ESA’s ESTRACK ground station network

Credit: ESA | Licence: ESA Standard Licence

El Hierro (Canary Islands, Spain) – Good azimuth, hard realization

Type: Spaceport (concept).

Strength: potentially excellent Atlantic trajectories.

Status (incl. estimated cadence): Concept/proposal stage; no licensing or build-out. Cadence: n/a until project advances.

Operator: INTA (Spanish National Institute of Aerospace Technology) – proposed the El Hierro Launch Centre as a civil spaceport for small polar and Sun-synchronous missions, but the project has so far remained at feasibility-study stage, with no construction or launch activity.

Tidbit: great geography isn’t enough – environmental and social factors set the pace.

Official site: (no dedicated official project site at this stage)

Western cliffs of El Hierro facing the Atlantic. The island has been studied as a potential site for a small launch centre

Western cliffs of El Hierro facing the Atlantic. The island has been studied as a potential site for a small launch centre

Photo: Eckhard Pecher, CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons

EuroSpaceport (North Sea, Denmark) – Offshore sea-based launch site under development

Type: Spaceport (proposed, offshore; suborbital first; orbital planned).

Strength: North Sea locations near Esbjerg with launch corridors almost entirely over water; focus on shallow-water areas and a mild maritime climate; concept leverages offshore platform know-how.

Status (incl. estimated cadence): In development. ESA-supported milestone via Boost! and a contract with SpaceForest; first sea-based PERUN suborbital mission planned for 2026 from “Spaceport North Sea.” The company indicates a 2026 mission window and active location studies. Cadence: n/a until permitting and construction.

Operator: EuroSpaceport – developer of an offshore launch system branded Spaceport North Sea, headquartered around Esbjerg; provides platforms, propellants, staffing, legal, and education services for launch campaigns.

Tidbit: Plans reference repurposing retired offshore wind-turbine infrastructure to create a cost-effective floating range.

Official site: eurospaceport.com

SUAS (Ireland) – Atlantic-facing concept for Irish launch sites

Type: Spaceport (concept)

Strength: Atlantic coastline enabling largely over-water flight corridors and high-latitude headings suitable for polar/SSO missions; Irish/EU setting and existing ground-segment ecosystem (company based at the National Space Centre, Cork).

Status (incl. estimated cadence): Early-stage proposal to develop two Irish spaceports; targets include an engine-test site (2025) and a first orbital micro-launcher flight (2026); currently fundraising (c. €5 m seed) and subject to licensing. Cadence: n/a at this stage.

Operator: SUAS Aerospace – Irish startup planning commercial spaceport facilities in Ireland

Tidbit: Ireland’s aviation regulator has already run a consultation on air-launched rocket operations in international airspace southwest of Ireland – a sign the regulatory groundwork for spaceflight is being explored.

Official site: suasaerospace.com

Space Tech Expo Europe 2025 (Bremen) – SUAS Aerospace actively present; visitors could speak with team members about plans and technology

Space Tech Expo Europe 2025 (Bremen) – SUAS Aerospace actively present; visitors could speak with team members about plans and technology

Photo by Tomasz Pac / Iterative Engineering

Beyond this map

The sites above are only part of Europe’s wider launch infrastructure.

Beyond vertical orbital and suborbital sites, there is Spaceport Cornwall in England (a horizontal spaceport that hosted Virgin Orbit’s first – unsuccessful – mission), historic test ranges such as El Arenosillo in Spain (a sounding rocket range, including the Miura 1 launch) and Salto di Quirra in Sardinia (a military range used, among other things, for Space Rider tests), as well as the German Offshore Spaceport Alliance concept, which proposes a mobile launch platform in the North Sea.

PLD Space’s MIURA 1 lifting off from the El Arenosillo Test Centre in Huelva, Spain – one of Europe’s long-standing sounding rocket and test ranges

PLD Space’s MIURA 1 lifting off from the El Arenosillo Test Centre in Huelva, Spain – one of Europe’s long-standing sounding rocket and test ranges

Photo: PLD Space, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Behind this new generation of European spaceports and launchers, one benchmark remains in the background: the Guiana Space Centre (CSG) in French Guiana.

Guiana Space Centre (Kourou, French Guiana) – Europe’s equatorial gateway to orbit

Type: Spaceport (equatorial; multi-launcher; orbital).

Strength: Near-equatorial location with launch azimuths over the Atlantic, ideal for GTO/GEO and low-inclination orbits; extensive ground infrastructure with multiple pads, long heritage, and established safety and range operations.

Status (incl. estimated cadence): Active. After Ariane 5’s retirement and a short gap, Ariane 6 was inaugurated from CSG in July 2024, with commercial missions following in 2025. Vega-C is planned to resume service from the site, while Ariane 6 is ramping up towards a target cadence of around 10–12 launches per year by 2027, consolidating CSG’s role as Europe’s primary orbital spaceport.

Operator: CNES / ESA / Arianespace – CSG is operated jointly by the French space agency CNES and ESA, with Arianespace providing commercial launch services for Ariane and Vega from the site.

Tidbit: CSG’s equatorial position allows significantly higher payloads to GTO than higher-latitude sites; between Ariane, Soyuz, and Vega, it has supported hundreds of missions and remains one of the busiest orbital launch sites in the world.

Official site: centrespatialguyanais.cnes.fr

Want to go deeper into CSG? If you’re interested in what day-to-day work at Europe’s Spaceport looks like, we’ve covered it in more detail in two separate articles: Europe’s Spaceport selected Iterative Engineering to improve the payload preparation process – how we helped streamline payload preparation workflows on the ground. LaunchReady: on-site simulation at Europe’s Spaceport – behind the scenes of rehearsing launch campaigns together with local teams.

Launchers: another way to map Europe’s access to space

Spaceports are only part of the story – launchers also shape where and how Europe can reach orbit or suborbital space, and many of them are not tied to a single site. Below, we look at several key programmes connected to the locations above: Poland’s PERUN suborbital rocket, the UK’s Skyrora family of small launchers, Spectrum from Isar Aerospace, the Miura line from PLD Space, Maia, Ariane 6, and Vega/Vega-C (Avio). Together they illustrate how Europe is developing both new and established launch vehicles to make use of – and in some cases expand beyond – its emerging network of spaceports, with the broader launcher landscape still evolving.

Perun (Poland) – Suborbital tech-demo platform from the Baltic coast

Type: Launcher (suborbital; not a spaceport)

Strength: purpose-built suborbital rocket for high-cadence technology demonstrations and research, launched over the sea from the Polish coast.

Status (incl. estimated cadence): active suborbital programme with iterative flights; pathfinder for future orbital competencies in Poland; (Nov 2025): SpaceForest completed Perun’s third suborbital test flight, marking another step toward higher-energy profiles and fulfilling the first milestone under ESA’s Boost! programme. Cadence: ~1–4/yr depending on campaigns/customers.

Operator: SpaceForest – company developing rocket technologies alongside microwave, electronics and AI-based solutions, offering design, prototyping and launch services for experiments on its in-house experimental rockets.

Tidbit: flights over the Baltic minimise populated overflight and provide rapid campaign learning for local industry.

Official site: spaceforest.pl/perun

Towards a Polish suborbital spaceport in Ustka

In Poland, PERUN is also at the centre of a broader discussion about creating a permanent suborbital spaceport at the Central Air Force Training Range in Ustka, on the Baltic coast. A parliamentary interpellation submitted in December 2025 (No. 14345) points to Ustka as the only site in the country with unlimited airspace over the sea and explicitly links it to ESA’s Boost! contract, which foresees at least four – and eventually up to ten – PERUN missions per year from 2027. If implemented, this would turn Ustka into a dual-use facility for civil microgravity research and defence-related trajectory tests, giving Central Europe its own dedicated suborbital launch site.

Perun suborbital rocket launching over the Baltic Sea from the Polish coast

Perun suborbital rocket launching over the Baltic Sea from the Polish coast

Image: SpaceForest (spaceforest.pl)

Skyrora (UK) – Microlauncher programme aligned with northern polar/SSO routes

Type: Launcher (small orbital and suborbital rockets; not a spaceport).

Strength: vertically integrated small-launcher development (3D-printed engines, Ecosene fuel) aligned with polar/SSO missions from northern sites (e.g., SaxaVord), with in-house engine and stage development to shorten iteration cycles.

Status (incl. estimated cadence): Engines and stages in qualification; ESA/UK-supported milestones; since August 2025, Skyrora also holds the UK’s first vertical launch operator licence for its suborbital Skylark L rocket, authorising up to 16 launches per year from SaxaVord; first orbital attempt TBD (mid-2020s target). Cadence after EIS: ~3–8/yr, subject to pad access (e.g., SaxaVord).

Operator: Skyrora – UK launch provider developing small orbital rockets, aiming to conduct the first vertical orbital launch from the UK and offer cost-effective, flexible access to space for global customers.

Tidbit: ecosene is produced from otherwise unrecyclable plastic waste; in-house metal additive manufacturing shortens iteration cycles.

Official site: skyrora.com

Skyrora XL – vehicle concept and development artwork

Skyrora XL – vehicle concept and development artwork

Image: ©ESA (ESA Standard Licence)

Isar Aerospace (Germany) – Small-sat launcher targeting flexible access from Andøya and beyond

Type: Launcher (small orbital rocket; not a spaceport).

Strength: Two-stage Spectrum vehicle designed to place up to ~1,000 kg into LEO or ~700 kg into SSO, with fully in-house development of engines, avionics, and structures to reduce cost and increase schedule control.

Status (incl. estimated cadence): First test flight of Spectrum from Andøya Spaceport on 30 March 2025 ended shortly after liftoff but provided valuable flight data; a second test window from Andøya is planned for January 2026. Long-term industrial plans point to a double-digit annual cadence once the system enters commercial service.

Operator: Isar Aerospace – Munich-based launch company developing the Spectrum small-sat launcher to provide dedicated orbital access from European spaceports such as Andøya.

Tidbit: Spectrum’s first flight was the first attempt at an orbital rocket launch from mainland Europe, marking a symbolic step for Europe’s private launch sector.

Official site: isaraerospace.com

Isar Aerospace’s Spectrum on the launch pad at Andøya Spaceport, Norway

Isar Aerospace’s Spectrum on the launch pad at Andøya Spaceport, Norway

Credit: © Isar Aerospace | Photo: Brady Kenniston (NASASpaceflight)

PLD Space (Spain) – From suborbital Miura 1 to orbital Miura 5

Type: Launcher (suborbital and orbital; not a spaceport).

Strength: Reusable small-launch family (Miura 1 suborbital demonstrator, Miura 5 orbital launcher) with strong vertical integration and dedicated test facilities, designed to offer Europe institutional and commercial access for small satellites.

Status (incl. estimated cadence): Miura 1 achieved Europe’s first private suborbital launch to space on 7 October 2023 from the El Arenosillo Test Centre in Spain. Miura 5 is in advanced development with engine and subsystem testing at Teruel and first orbital launches targeted from the Guiana Space Centre around 2026; industrial plans envisage scaling towards dozens of launches per year by 2030.

Operator: PLD Space – Spanish launch company developing the Miura family and operating extensive test infrastructure in Elche, Teruel, and Kourou to support suborbital and orbital missions.

Tidbit: Miura 5 has been pre-selected under ESA’s European Launcher Challenge and is positioned as a European competitor in the small-launcher market.

Official site: pldspace.com

PLD Space’s MIURA 1 rocket

PLD Space’s MIURA 1 rocket

Credit: PLD Space, “Miura 1, PLD Space, España, 2017”, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

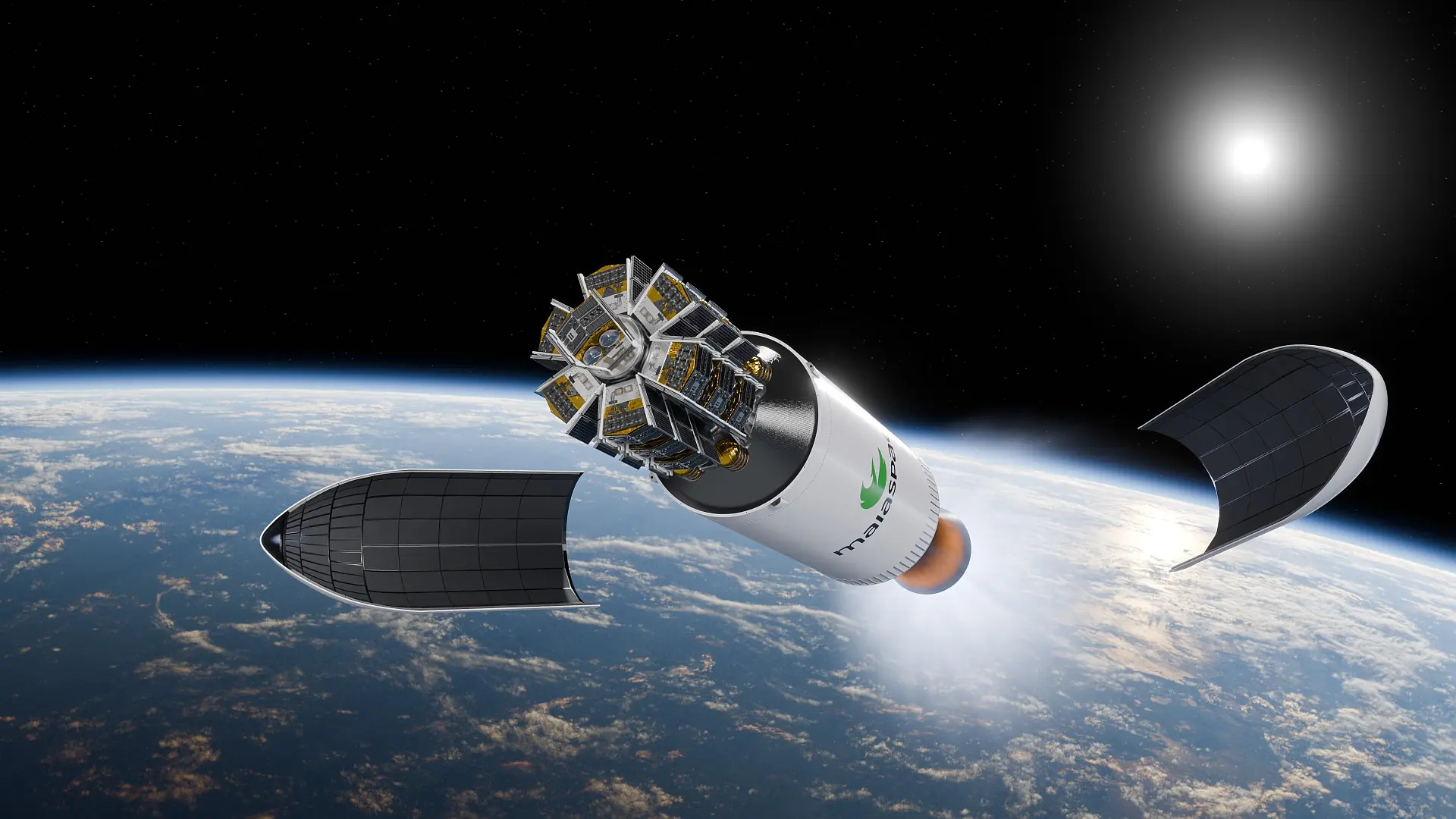

MaiaSpace / Maia (France/Europe) – Reusable methane launcher built around Prometheus

Type: Launcher (partially reusable orbital rocket; not a spaceport).

Strength: Two-stage Maia launcher powered by Prometheus® methane-LOX engines, designed from day one in both reusable and expendable versions to serve different satellite mass ranges from a single core design.

Status (incl. estimated cadence): In development, with first flights planned from the Guiana Space Centre’s ELS site around 2026. As a next-generation system, Maia is intended to demonstrate reusability and eventually support a regular institutional and commercial cadence once operational.

Operator: MaiaSpace – a wholly owned ArianeGroup subsidiary focused on sustainable, partially reusable launch systems and related in-space mobility services.

Tidbit: Maia is the first European start-up launcher designed around the Prometheus® reusable engine, a flagship ESA/ArianeGroup technology demonstrator for low-cost methane engines.

Official site: maia-space.com

MaiaSpace concept illustration: payload fairing separation

MaiaSpace concept illustration: payload fairing separation

Credit: MaiaSpace (via Eutelsat / Mynewsdesk) – Media Use (unmodified)

Ariane 6 (Europe) – Heavy-lift backbone for Europe’s institutional missions

Type: Launcher (heavy-lift orbital rocket; not a spaceport).

Strength: Modular Ariane 6 (A62/A64 variants) providing multi-tonne payload capacity to GTO, GEO, and LEO from the equatorial Guiana Space Centre, designed to serve large institutional missions and constellations with a higher cadence than Ariane 5.

Status (incl. estimated cadence): After its inaugural test flight in July 2024, Ariane 6 entered commercial service in 2025, including a first commercial mission carrying the CSO-3 military satellite and subsequent Galileo launches. By the end of 2025 the vehicle had flown multiple times, and Arianespace is targeting 6–8 launches in 2026 and around 10–12 launches per year from 2027 onward, with more than 30 missions already sold.

Operator: ArianeGroup / Arianespace – ArianeGroup develops and builds Ariane 6, while Arianespace markets and operates it from CSG as Europe’s primary heavy-lift launcher.

Tidbit: Ariane 6, together with Vega-C, restores Europe’s autonomous access to space after the retirement of Ariane 5 and the loss of Soyuz from CSG.

Official site: ariane.group (launcher) / arianespace.com (launch services)

Ariane 6 climbs away from Europe’s Spaceport on its inaugural flight

Ariane 6 climbs away from Europe’s Spaceport on its inaugural flight

Credit: © ESA – S. Corvaja (ESA Standard Licence)

Vega / Vega-C (Italy/Europe) – Europe’s institutional small-sat workhorse

Type: Launcher (small/medium-lift orbital rockets; not a spaceport).

Strength: The Vega family (Vega and its upgraded Vega-C variant) offers dedicated access for small and medium institutional payloads to polar, Sun-synchronous, and low Earth orbits, with the ability to deploy multiple satellites via SSMS rideshare missions from the Guiana Space Centre.

Status (incl. estimated cadence): Original Vega has now been retired; Vega-C returned to flight in December 2024 with Sentinel-1C and flew additional missions in April and July 2025, including Biomass and the CO3D/MicroCarb satellites. Vega-C is active and ramping up under a model where Avio increasingly commercialises the launcher directly; future upgrades (Vega-E, Vega-C+) and boosters (P160C) are planned for later in the decade.

Operator: Avio – Italian prime contractor and manufacturer for Vega and Vega-C, responsible for development and, progressively, commercial operations, with launches conducted from CSG’s ELV/ZLV complexes.

Tidbit: Vega-C can lift about 2.3 tonnes to SSO – roughly 60% more than the original Vega – and shares its P120C first-stage motor with Ariane 6, spreading development costs across both launcher families.

Official site: avio.com (Vega family overview) / Vega-C (ESA launcher page)

Vega-C lifts off from Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana

Vega-C lifts off from Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana

Credit: © ESA – M. Pedoussaut (ESA Standard Licence)

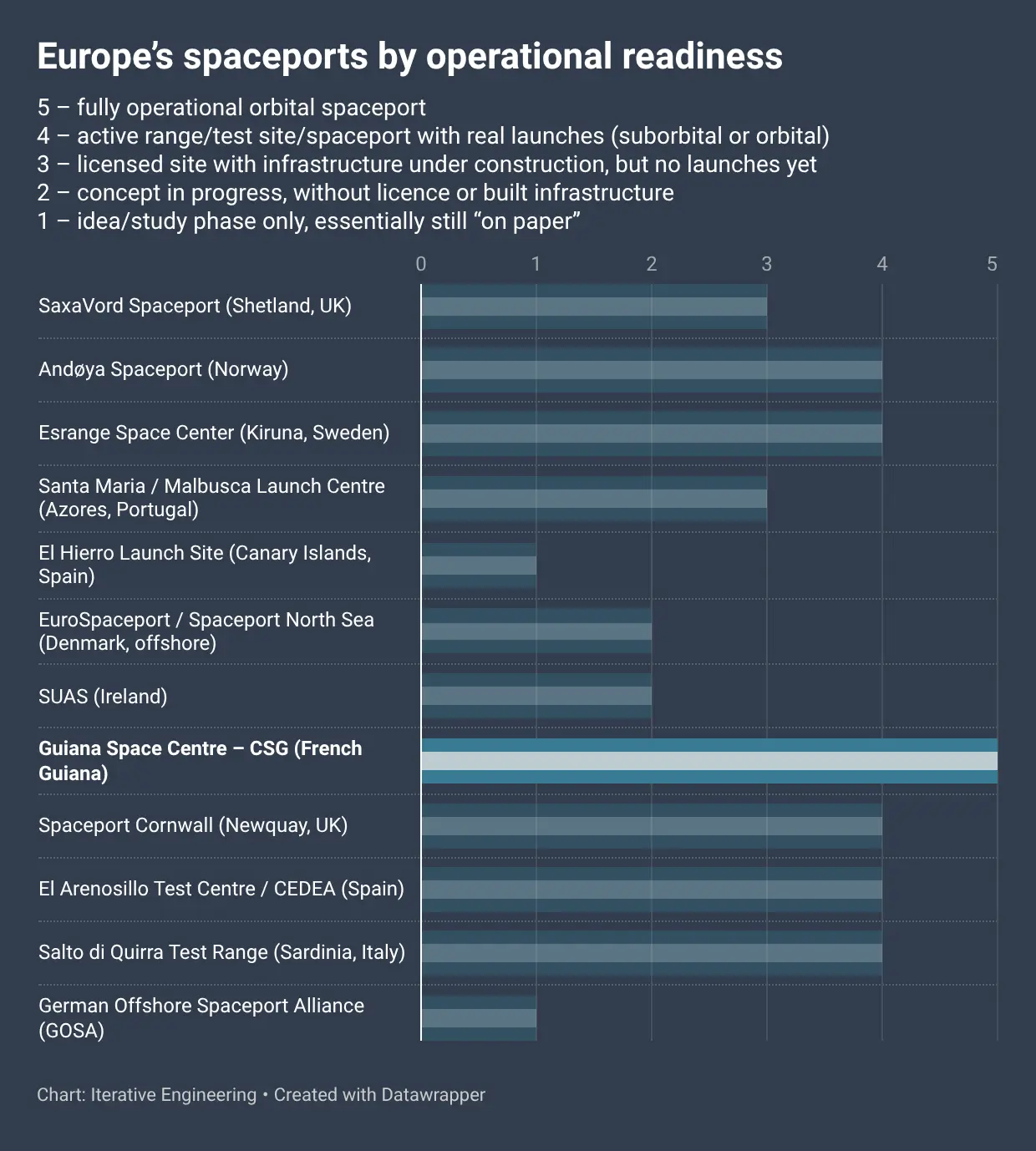

Not all European launch initiatives are at the same stage. This chart ranks selected spaceports and launch programmes by how close they are to regular operations – from active, licensed sites to early-stage concepts.

Picking the right vertical port (a practical cheat sheet):

- Small EO payload to SSO/Polar → SaxaVord or Andøya (north, ocean-facing corridors).

- High-tempo tech demos (suborbital) → Perun flights over the Baltic (rapid iterations).

- R&D transitioning to orbit → Esrange (strong test backbone + new orbital pad).

- Future Atlantic corridor → Santa Maria (as infrastructure comes online).

Why we’re following Europe’s spaceports

At Iterative Engineering, we follow Europe’s emerging spaceports closely because part of our work involves building software around launch campaigns, ground operations, and data flows with European partners. This article is meant as a straightforward overview for people who keep an eye on Europe’s launch ecosystem. Whether you work in the sector or are simply trying to understand what’s coming next, if you spot anything that needs updating or feel a site is missing, we’re always happy to compare notes.

Iterative’s CEO in discussion with a SaxaVord Spaceport representative at Space Tech Expo Europe 2025 – one of several conversations we had with European launch sites during the event

Iterative’s CEO in discussion with a SaxaVord Spaceport representative at Space Tech Expo Europe 2025 – one of several conversations we had with European launch sites during the event

Photo by Tomasz Pac / Iterative Engineering

Hero image: Andøya Spaceport – the Spectrum rocket just after liftoff

Photo: Isar Aerospace / Simon Fischer – Wingmen Media. Editorial use only; do not alter/remove copyright notices

- Why more than one vertical port?

- Getting oriented in orbit: the essentials

- Beyond the basics (common destinations for heavier launchers)

- Who excels at what – and where to click for more

- SaxaVord (Shetland, UK) – Northern hub for vertical launches

- Andøya (Norway) – From mature suborbital base to orbital readiness

- Esrange (Kiruna, Sweden) – From research range to regular orbital missions

- Santa Maria (Azores, Portugal) – An Atlantic pad in deployment

- El Hierro (Canary Islands, Spain) – Good azimuth, hard realization

- EuroSpaceport (North Sea, Denmark) – Offshore sea-based launch site under development

- SUAS (Ireland) – Atlantic-facing concept for Irish launch sites

- Beyond this map

- Guiana Space Centre (Kourou, French Guiana) – Europe’s equatorial gateway to orbit

- Launchers: another way to map Europe’s access to space

- Perun (Poland) – Suborbital tech-demo platform from the Baltic coast

- Towards a Polish suborbital spaceport in Ustka

- Skyrora (UK) – Microlauncher programme aligned with northern polar/SSO routes

- Isar Aerospace (Germany) – Small-sat launcher targeting flexible access from Andøya and beyond

- PLD Space (Spain) – From suborbital Miura 1 to orbital Miura 5

- MaiaSpace / Maia (France/Europe) – Reusable methane launcher built around Prometheus

- Ariane 6 (Europe) – Heavy-lift backbone for Europe’s institutional missions

- Vega / Vega-C (Italy/Europe) – Europe’s institutional small-sat workhorse

- Why we’re following Europe’s spaceports