Payload preparations at the Guiana Space Centre: what does preparing a satellite for the launch look like?

Before a satellite reaches the launch pad, it is built independently of the launch vehicle. The integration process begins in the preparatory infrastructure: in processing halls, airlocks, transfer corridors, security zones, and control rooms.

In this article, we describe these preparations step by step, mainly using the example of the Guiana Space Centre (CSG) in Kourou, based on an Iterative Engineering project in this area, our visit to the Europe’s Spaceport, and many conversations with Payload Preparation Managers (RMCU) and other teams involved in the process. Although the CSG is the point of reference, we also consider the broader context of satellite campaigns, including rideshare and the role of payload distributors.

It is also worth setting the scale right away, because this is not a process that happens “on a whim.” In 2025, there were 7 orbital launches in Kourou – yet the number of payload preparation campaigns at CSG can reach the dozens each year, since a single launch may involve multiple payloads and separate processing flows. Looking ahead, CNES is preparing a major ramp-up in operational bandwidth and launch tempo at CSG, including ELM (fr. Ensemble de Lancement Multi‑lanceurs) at the former Diamant area (a multi-user complex for small launchers) and a broader cadence increase tied to Ariane 6. And that is still only one spaceport within a much broader global cadence of launch campaigns. This calls for operating in a repeatable, auditable, and schedule-resilient way.

Load scale: from 1U to several tons

In the public sphere, “satellite” is sometimes used as a catch-all term. At the campaign level, this word covers a wide range of sizes and operating scenarios.

On the one hand, there are CubeSats: the 1U standard is a cube measuring approximately 10 × 10 × 10 cm, with typical weight limits of around 1 to 1.33 kg. And although such a load can theoretically be carried by hand, this does not shorten the list of requirements regarding access zones, cleanliness, ESD, configuration control, or documentation.

A Fly Your Satellite! student signs the mission logo on the Ariane 6 fairing at Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou, marking a memorable moment in the launch campaign ahead of Ariane 6’s inaugural flight

A Fly Your Satellite! student signs the mission logo on the Ariane 6 fairing at Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou, marking a memorable moment in the launch campaign ahead of Ariane 6’s inaugural flight

Credit: Photo – © ESA / CNES / Arianespace / ArianeGroup (ESA Standard Licence)

Even in the case of CubeSats, their “smallness” quickly disappears once the actual launch campaign begins. For Ariane 6’s inaugural flight, the student-built satellites 3Cat-4 and ISTSat-1 arrived at CSG already mounted inside their orbital deployer, after being integrated at Exolaunch’s facility in Berlin a few weeks earlier.

The deployer is essentially the “flight container” and release mechanism – a shared mechanical/electrical interface that keeps multiple CubeSats secured on the ground, then deploys them safely in orbit. On-site, the teams completed spaceport safety training and joined the campaign flow. Before mating, the deployer went through inspections and functional checks, and a Combined Operations Readiness Review cleared the payloads for installation on the launch vehicle adapter as part of the upper composite. As a memorable campaign tradition, the teams involved in Ariane 6’s inaugural mission were even invited to sign the mission logo on the fairing before it moved on to final assembly and closure.

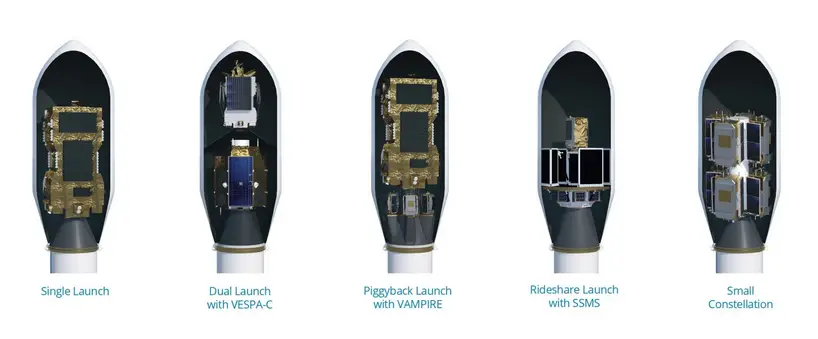

That CubeSat example hints at a broader point: at a spaceport, “the payload” is often a configuration rather than a single spacecraft. Depending on the mission, teams may work around a classic single launch, a dual launch structure, piggyback setups, or multi-payload dispensers – and each option changes the mechanical interfaces, access constraints, and the day-to-day campaign flow.

Different payload configurations you can encounter during a launch campaign – from a single spacecraft to dual and piggyback setups, rideshare dispensers (SSMS), and small constellations

Different payload configurations you can encounter during a launch campaign – from a single spacecraft to dual and piggyback setups, rideshare dispensers (SSMS), and small constellations

Next comes the world of small satellites and constellations. In the rideshare model, the importance of dispensers is growing – mechanical intermediate structures that collect multiple payloads and then release them into orbit in a planned sequence. In the European ecosystem, a good example is SSMS (Small Spacecraft Mission Service) for Vega: we are talking about missions in which more than 50 satellites were launched in a single flight.

Exolaunch NOVA CubeSat deployer/deployer family – hardware used to carry, handle, and deploy CubeSats during rideshare launch campaigns

Exolaunch NOVA CubeSat deployer/deployer family – hardware used to carry, handle, and deploy CubeSats during rideshare launch campaigns

Credit: Photo – © Paweł Grzywocz/Iterative Engineering

Rideshare and the dispenser: one campaign can involve dozens of payloads – and with them, multiple teams, interfaces, and access constraints

Rideshare and the dispenser: one campaign can involve dozens of payloads – and with them, multiple teams, interfaces, and access constraints

Credit: Photo – © ESA / M. Pedoussaut (ESA Standard Licence)

One flight can mean a really large number of objects: there are missions outside Kourou in which over 100 satellites were launched (e.g., PSLV-C37 from 2017 – 104 satellites). This may not be an everyday occurrence yet, but it clearly shows how much logistics change when the number of teams and parallel integrations increases.

At the other end of the spectrum are large telecommunications and observation platforms, weighing many tons in their launch configuration. For comparison, the James Webb Space Telescope weighed about 6.2 tons. On this scale, a single “step” of a campaign can be a project in itself, because the margin for error is then minimal.

The road to Kourou: express air freight or a voyage across the Atlantic

While still on Earth, the satellite is never alone in its journey. It is accompanied by a team of highly skilled engineers, usually the same people who took part in designing and building it. They arrive at the spaceport days or weeks before the spacecraft shows up in French Guiana, but the campaign planning starts long before. Each person of the team has a set of designated tasks that they need to complete. The goal is simple – make sure that the precious cargo is not damaged during its journey and prepare it for takeoff. The CSG welcomes many guests each year, with the satellite teams ranging around 10-20, depending on the size of the mission.

As our CTO recalls:

During the workshops collecting requirements for the Campaign Management tool, we asked about the largest number of people that took part in a single campaign. The Payload Facility Manager recalled the ATV, which was a cargo ship heading to the International Space Station. It was one of the biggest campaigns they had – it lasted around 6 months and involved multiple teams of around 10 people, switching through monthly shifts (so around 60 people in total)!

– Paweł Grzywocz

The spacecraft does not arrive in French Guiana “in a shoe box.” The standard procedure involves a special transport container and logistics, where the key factor is not the transport itself, but maintaining a stable environment: temperature, humidity, shock control, and events along the way.

Air freight to the spaceport: oversized cargo aircraft and dedicated ground handling are part of the campaign logistics

Air freight to the spaceport: oversized cargo aircraft and dedicated ground handling are part of the campaign logistics

Credit: Photo – © ESA / EADS Astrium / Raoul Kieffer (ESA Standard Licence)

Therefore, before the container is even opened, teams check the recorded travel parameters. For delicate cargo, the journey to the spaceport itself is part of the campaign, and work at the CSG can take weeks – especially when the plan includes additional tests, repairs, or an unusual integration sequence.

Sea freight to Kourou: dedicated vessels and port operations at Pariacabo are the “quiet” backbone behind launch campaigns

Sea freight to Kourou: dedicated vessels and port operations at Pariacabo are the “quiet” backbone behind launch campaigns

Credit: Photo – © ESA / J. Corvaja

And then there is the context that can be physically felt in French Guiana: the tropics. Heat and rain are a real part of the infrastructure, and insects and humidity are a constant feature of the work. The vehicles and facilities, protecting the precious payload, have to withstand these conditions. Even the rockets must be hardened sometimes – for example, in the Soyuz campaigns in Kourou, measures were implemented to reduce the risk of tropical insects entering sensitive areas (e.g., openings were secured, additional cleaning was carried out, and traps were set).

Galileo L14 satellites transfer at Europe’s Spaceport (CSG), Kourou. The payload was moved in its transport container from the S1A facility to S5A as part of the VA266 campaign – Ariane 6’s fourth commercial mission

Galileo L14 satellites transfer at Europe’s Spaceport (CSG), Kourou. The payload was moved in its transport container from the S1A facility to S5A as part of the VA266 campaign – Ariane 6’s fourth commercial mission

Credit: Photo – © CNES / ESA / Arianespace–ArianeGroup / Optique Vidéo CSG / S. Martin, 2025

EPCU at CSG: where payload preparation begins

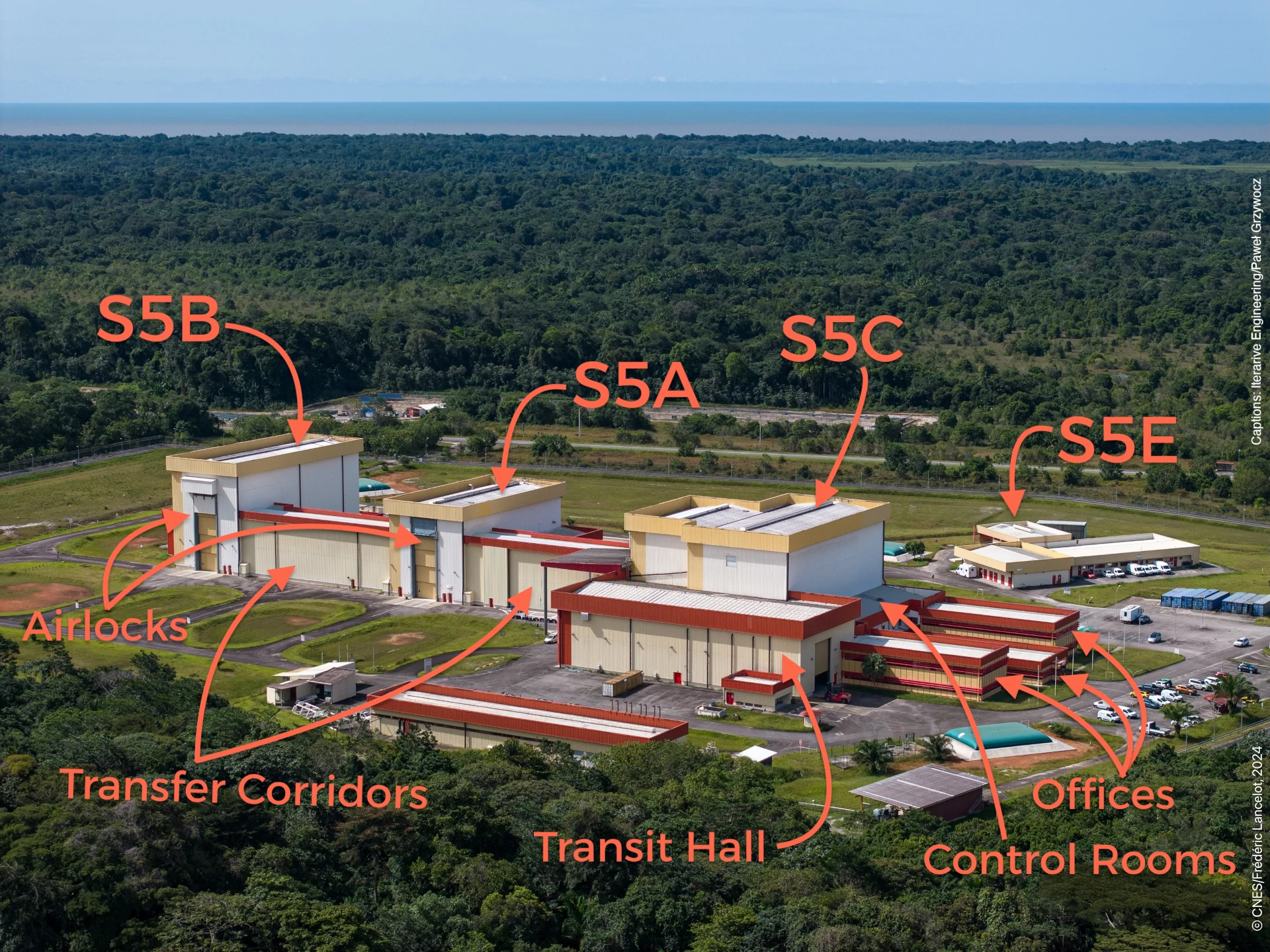

CSG has a complex of facilities for payload preparation, internally called EPCU (fr. Ensemble de préparation des charges utiles). In practice, the campaign very quickly descends to the level of specific buildings and their “profile.”

To put it simply:

- the S1 and S3 complexes are typically used for less demanding operations (e.g., integration, testing, check-out, preparation),

- the S5 complex is designed for hazardous operations (including those related to fuels), and at the same time has large, more modern spaces and extensive transfer logistics, which can accommodate larger spacecraft.

S5 at Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou: a key facility for hazardous operations and high-rigor payload processing

S5 at Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou: a key facility for hazardous operations and high-rigor payload processing

Credit: Photo – © CNES / Frédéric Lancelot

We had the opportunity to see elements of the process in S1 and S5 “from the inside” (including the logic of moving between zones, airlocks, part of the control infrastructure, and how the work of many teams is organised simultaneously).

Behind these halls and corridors lies a role that is rarely talked about openly, but without which the campaign simply cannot maintain its momentum: the Payload Facility Manager, or RMCU (fr. Responsable moyens charges utiles). On the CSG side, this function is responsible for the “means” of preparing the payload – in practice, ensuring that the infrastructure is ready, available, and secure on time. This includes coordinating activities at the EPCU, adapting facilities to customer needs, ongoing coordination between teams, and finalizing campaign data and confirmations – often as the first point of contact on the spaceport side.

Transit Hall: unloading and the way to the airlock

The satellite arrives in a special transport container. The first stop is not immediately the clean room, but the reception area – often called the Transit Hall. This is a covered buffer space that protects the cargo and crew from the weather and allows initial activities to be carried out before opening the way to areas with higher requirements.

In the next stages, safe transfer becomes crucial: how to lift, move, and bring the cargo into the next zone without compromising the conditions. Cranes, forklifts, special tools, sometimes air cushions, and dedicated transport trolleys are used for unloading and transfer.

Sentinel 1-D Container entering the Transit Hall in S5

Sentinel 1-D Container entering the Transit Hall in S5

Credit: Photo – © CNES / ESA / Arianespace / Optique Vidéo CSG / C. Gallo, 2025

Air lock: controlled transfer between zones

Access to the relevant preparation zones is provided via airlocks. In spaceports, an airlock is a controlled transfer space with its own logistics, checkpoints, and environmental regime. The attention to detail is incredible. For example, we saw hat-like covers with a brim and transparent protective rings around crane components, all meant to prevent anything from dripping onto the satellite. That same mindset carries into the transfer interfaces themselves. Even trace amounts of grease or metal filings can cause problems, because the hardware is both delicate and extremely expensive.

To give a sense of scale, at CSG, airlocks measuring 30 × 20 m are not unusual. In practice, the flow is split: personnel enter through dedicated gowning/entry points, and only after passing through the personnel airlock do they enter what most people call the “clean room.” Entry typically involves lockers, changing clothes, protective gear, ESD control, and often an air shower to blow dust and particles off protective clothing. Payloads and equipment move through larger, controlled transfer routes designed for trolleys, containers, and lifting operations.

In effect, the airlock acts as a buffer: it allows the cleanest areas to be “cut off” while operations continue smoothly. There have been situations where transfer-zone doors were physically open to the outside, and the required level of cleanliness was still maintained through overpressure, filtration, and practical measures like additional cleaning, flow control, and insect protection.

One more constraint is less visible: radiofrequency emissions. According to on-site accounts, during an exceptionally sensitive campaign, transfers were coordinated so nearby radar activity was temporarily reduced or paused before opening the airlock, out of caution that strong RF emissions could interfere with delicate electronics or instruments.

(CSG operates several tracking radars; for example, the Bretagne 1 radar, capable of generating a 1-MW electromagnetic wave.)

Sentinel-2C satellite entering the Airlock at S1A, from the CCU3 transporter docked to the door.

Sentinel-2C satellite entering the Airlock at S1A, from the CCU3 transporter docked to the door.

Credit: Photo – © CNES / ESA / Arianespace / Optique Vidéo CSG / T Leduc, 2024

Clean room: coveralls, air shower, and… manual dust counting

The clean rooms are the heart of the payload preparation facilities. This is where all the work happens – from inspections, through final assembly, to fuelling. All the people and tools need to undergo special procedures to enter.

You cannot simply enter the cleanroom, even if it’s currently not in use. You need at least a protective cap and shoe covers with antistatic straps. While visiting S5B, when we were putting on the “bunny suits” before entering the airlock, we even had to follow a special set of moves – a cover and one leg first, over the counter, and then followed by the second leg. All to minimise the chances of contamination.

– Paweł Grzywocz

The following things are key in the halls themselves:

- airborne particle control (sensors, monitoring),

- overpressure to “push” air out instead of sucking contaminants in,

- and constant, tedious work hygiene: equipment, surfaces, and how tools are brought in.

An interesting fact that illustrates the level of rigor: cleanrooms operate within defined cleanliness classes (ISO 14644-1), meaning there are hard limits on how many airborne particles of a given size can be present per cubic metre of air. In practice, the environment is continuously monitored with laser-based airborne particle counters that sample a known airflow and flag deviations quickly, not just at the end of the day.

Alongside these electronic readings, teams may still place witness plates – defined sampling surfaces that “collect” particle fallout over time – and then inspect them with optical/microscope-based methods. This gives an independent cross-check (and often an archival record) of what was actually deposited on surfaces during critical phases, which is especially valuable when contamination control extends beyond the main cleanroom into transfers and later integration steps.

Those facilities involve more clever engineering, such as a central vacuum cleaner built into the wall, so that the cleaning crew does not bring in mobile equipment on wheels that could stir up dust. Or huge blinds that can be used to divide the clean room into two independent work zones (e.g., when work is being done on two payloads at the same time), and covered windows in offices to reduce the risk of “spying” on competitors’ solutions.

And even though French Guiana is a very seismically calm place, you still need to think about the ground movements – that’s why there’s also a metal vibration-damping plate embedded in the floor, used to isolate the load from shocks and vibrations during work in the hall.

The James Webb Space Telescope inside the cleanroom at EPCU S5B, being prepared for fuelling.

The James Webb Space Telescope inside the cleanroom at EPCU S5B, being prepared for fuelling.

Credit: Photo – © CNES / ESA / Arianespace / Optique Vidéo CSG / P Piron, 2024

Solar arrays and onions: life between critical steps

The office spaces adjacent to the payload facilities can also host multiple teams at the same time. The space can be divided by moveable walls to ensure confidentiality. What you can certainly feel while being inside is the pride and heritage that this place carries. Hundreds of small and big missions took place there, and the spacecraft teams have left behind their mission stickers. The walls in some corridors and visitor spaces are covered with photos of those spacecraft.

During a launch campaign, teams can be on site for weeks, working in a tight rhythm and under real schedule pressure. That’s why day-to-day practicality matters so much: fatigue, haste, and small decisions can quickly turn into real operational risk.

In conversations on site, one example that came up was an incident where parts of a satellite’s solar arrays were accidentally damaged by the satellite team during handling. Even though such incidents are generally very rare, the spaceport staff must be prepared for the unexpected and ready to help their guests even in unusual situations.

And on the lighter end of the spectrum, there’s a local legend that almost everyone seems to know: once, the team working on the satellite was so slammed that someone set up an improvised “meal prep” on the floor in an office area next to the cleanroom and started chopping an onion for dinner. Funny – but it captures the reality of campaign work: not just a checklist, but everyday life squeezed between critical steps.

The office buildings at the entrance of the EPCU S5 complex.

The office buildings at the entrance of the EPCU S5 complex.

Credit: Photo – © CNES / ESA / Arianespace / Optique Vidéo CSG / P.Baudon - E.Prigent, 2021

Satellite check-out: tests, measurements, and go/no-go decisions

The actual engineering work takes place in clean rooms and adjacent laboratories: electrical and mechanical tests, measurements, check-outs, and preparation of the launch configuration. A good illustration comes from another ESA campaign. A typical check-out phase includes very specific, risk-driven tests.

For example, in the Sentinel-1C campaign, this meant nitrogen pressurisation of the fuel tank to check for leaks, broad functional tests of subsystems, and payload health checks – such as installing waveguide bridges on the stowed SAR antenna – while the other team, located in another part of the globe (at ESOC in Darmstadt) simultaneously validated telemetry on the operations side – a setting we’ve also had the chance to experience firsthand through ESA’s Mission Operations Academy at ESOC.

Control Room at ESA’s European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) in Darmstadt, Germany

Control Room at ESA’s European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) in Darmstadt, Germany

Credit: Photo – © Krzysztof Gąsior / Iterative Engineering

The CSG infrastructure includes mechanical and chemical laboratories, areas for weighing, environmental parameter control, electromagnetic compatibility testing, and a range of verification activities.

A typical check-out phase also includes high-pressure safety work on the propulsion side. In one Meteosat campaign at CSG, the teams first validated the EGSE, then ran a pressurisation/depressurisation sequence to confirm the tanks were leak-tight – while partially loading the helium system (50% level, reported as 133 bar), which required installing blast shields around the spacecraft as an added safety layer. These operations are tightly coordinated with the spaceport safety chain (including the CSG Safety Officer), and only after a clean result does the campaign move on to the next steps.

An important element of this puzzle is the check-out rooms, where the mission team sits and monitors the satellite’s parameters. This is where the cables from the cable passages between the office and the hall end, where the monitoring equipment is located, and where decisions are made: whether to continue or to pause the sequence and return to diagnostics.

And there is one more thing that usually surprises outsiders: gases. They appear not only in the context of rockets.

- Inert gases (most often nitrogen) are used for inerting – filling workspaces with inert gas to reduce the risk of ignition or unwanted reactions.

- Electric-powered missions use noble gases as fuel; for example, the BepiColombo mission loaded 581 kg of xenon.

Transport between facilities: CCU and the logic of “sealed transfer”

As we already described, CSG is not a single building, but a set of facilities, and a campaign may require the transfer of cargo between halls or complexes. This is done using specialized payload containers, called CCU (fr. Conteneurs de charges utiles), in versions adapted to different sizes and scenarios.

CCU2 Taking the satellite 30/MEV-2 out of CCU2 in BAF. Note the stickers and writings on the walls, commemorating all the missions that rode on that transporter vehicle

CCU2 Taking the satellite 30/MEV-2 out of CCU2 in BAF. Note the stickers and writings on the walls, commemorating all the missions that rode on that transporter vehicle

Credit: Photo – © CNES / ESA / Arianespace / Optique Vidéo CSG / P. Piron, 2020

Apart from the rocket parts moving through the spaceport, this is the other characteristic element of some roads in Kourou: a huge, mobile container that can drive up to a building and create a sealed transfer connection. The CCU3 version uses inflatable seals that ensure tightness and support the maintenance of a controlled environment (e.g., by maintaining pressure differences and limiting the inflow of outside air).

Operator controlling the self-propelled CCU3 transporter before docking into the S5B airlock

Operator controlling the self-propelled CCU3 transporter before docking into the S5B airlock

Photo – © CNES / ESA / Arianespace / Optique Vidéo CSG / P. Baudon, 2021

How does it work in practice? The transporter pulls up sideways to the door of the selected facility and “attaches” itself to the gate with a tight flange/seal. Once the connection is ready, the roller shutter is retracted, and the load can be transferred without exposing it to external conditions. This mechanism, seemingly simple, is crucial in the tropics: it limits the impact of humidity, temperature, and unwanted contaminants, while allowing the transfer of objects of extremely large dimensions.

Two interesting facts about the location:

- CCU transporters are often densely covered with mission logos and team signatures. Over time, this has become a local tradition – so much so that there have reportedly been less diplomatic additions (e.g., addressed to superiors), which has forced greater control over what ends up on the vehicle’s exterior.

- We also learned how varied the scenarios can be. James Webb was so large that it did not fit in the internal corridor connecting the halls of the S5; it had to be transferred in an unusual way, using external transport between buildings.

Transporting the satellite between S5B and S5C using the clean corridor

Transporting the satellite between S5B and S5C using the clean corridor

Credit: Photo – © CNES / ESA / Arianespace / Optique Vidéo CSG / S. Martin, 2025

Hazardous operations: pyrotechnics, blast shields, and hypergolic fuels

At some point in the campaign, activities arise that require a completely different “layer” of safety. At CSG, the natural environment for such stages is the S5 complex, which includes zones and halls prepared for hazardous operations. However, before the container reaches a clean hall, it enters the spaceport’s access-controlled zone. It goes without saying that CSG is a high-security, tightly controlled site, with checkpoints, restricted roads, and tightly managed movement of people and vehicles. Security is provided not only through badges and procedures – the French Foreign Legion guards the area, and a specialised on-site fire brigade also has law-enforcement powers. In practice, this adds a very real operational layer: convoys, access windows, and permitted locations and timings are part of the campaign plan.

Pyrotechnics and blast shields

Many satellites have pyrotechnic components because separation must be performed after launch. If the payload is mechanically bolted to the adapter and then needs to be detached in space, mechanisms are needed that will work reliably in all conditions. In practice, this also means working with components that are treated as hazardous materials on the ground. This is where blast shields come in – we saw them on site as structures resembling metal “chain mail,” whose task is to limit the effects of a possible unplanned detonation.

Refuelling: the stage where “spacesuits” and ATEX regulations come into play

Hypergolic fuels are commonly used in satellite campaigns – pairs of components that ignite spontaneously on contact (without an igniter). A classic example is hydrazine (or its derivatives) and an oxidizer in the form of nitrogen oxides/dinitrogen tetroxide. This is convenient in space (reliable ignition), but on Earth, it means strict logistics and safety measures. Fuelling is carried out in a dedicated facility, separate from other parts of the spaceport. Before any propellant is loaded, the pressurised system is pressure-tested to rule out leaks – only then can the team proceed. Because hydrazine is both highly toxic and explosive, only a small number of specialists remain inside the cleanroom, protected by SCAPE suits (Self-Contained Atmospheric Protection Ensemble). For example, in the Sentinel-1C campaign, this step involved loading 154 kg of propellant after the Flight Readiness Review, with the process run as combined operations and parameters continuously tracked on the fuelling gauges.

SCAPE suits during hydrazine fuelling preparations. It may look like sci-fi — in reality it’s standard PPE for a high-risk step

SCAPE suits during hydrazine fuelling preparations. It may look like sci-fi — in reality it’s standard PPE for a high-risk step

Credit: Photo – © ESA / CNES / Arianespace / Optique Vidéo du CSG / P. Baudon

At S5, there are practical safety rules that stick in your mind: for example, how to park at certain halls (car facing the exit, windows closed) so that in the event of a leak, you can immediately drive away and switch the car to closed circulation.

Mating: satellite on the adapter

Once the payload is ready, it is time for the mechanical connection to the payload adapter – a structure that connects the satellite to the upper stage of the rocket.

The payload adapter is more than just a mounting ring: it is a structural interface that takes on loads during launch and a separation system that must release the spacecraft with precision. It is usually an adapter with separation elements designed to provide the spacecraft with a minimum relative separation velocity of approximately 0.5 m/s. During the time of the Sentinel-2C campaign, the teams could still keep the satellite powered and run checks via umbilical lines routed through the adapter. At that point, the adapter was already an active interface – not just a metal component.

Mechanical integration (fit check): the spacecraft is aligned with the launcher adapter while teams verify interfaces and readiness – a step dominated by tooling, torque, verification, and configuration control

Mechanical integration (fit check): the spacecraft is aligned with the launcher adapter while teams verify interfaces and readiness – a step dominated by tooling, torque, verification, and configuration control

Photo – © ESA (ESA Standard Licence)

Encapsulation: the fairing as a controlled environment

In the European rockets used in Kourou (Vega-C and Ariane 6), the fairing is assembled from two large half-shells that are closed and locked as part of the integration process.

The fairing is primarily an aerodynamic cover, but it is also designed to maintain controlled conditions (temperature, humidity, cleanliness) and protect the payload both on the ground and during the first minutes of flight. This is especially important in such a hot and humid environment as French Guiana, as it is the only barrier that keeps the precious satellite dry, cool and free of (insects wanting to hitchhike on it).

PAC (Payload Assembly Composite – the spacecraft encapsulated within a fairing) exiting S5B

PAC (Payload Assembly Composite – the spacecraft encapsulated within a fairing) exiting S5B

Credit: Photo – © CNES / ESA / Arianespace / Optique Vidéo CSG / J.-M. Guillon, 2024

Once the spacecraft is encapsuled within the fairing, it is ready to leave the Payload Preparations Facilities to be placed on top of the rocket. This is the moment when the payload preparation process typically ends. But the satellite team doesn’t leave the complex yet. The most important step in the satellites journey is about to begin!

During the launch sequence, the satellite team stays at EPCU and monitors the spacecraft to make sure that everything is in order, up to the very seconds before the ignition. They keep a close contact with the DDO (Range Operations Manager) and take part in the go/no-go poll. They even have their own well-known “big red button”, that can abort the launch if they spot anything off-nominal.

How the software can support the payload preparation?

The process is complex, and good oversight is what keeps it from drifting into avoidable delays and rework. The biggest risks rarely come from one “big step” – they come from intersections: people, zones, tools, permissions, deliveries, schedule changes, and dependencies between tasks happening in parallel.

That’s why, working closely with CSG, Iterative Engineering developed a digital platform to support campaign and service management across the spaceport’s preparation facilities. The platform ties a service catalogue to request intake and tracking, giving customers and CSG teams a shared view of status, ownership, and blockers. It strengthens traceability, makes oversight clearer, and supports configurable automation across different campaign setups – which matters when similar workflows have to adapt to different payloads, constraints, and timelines.

Hero image: The James Webb Space Telescope is unpacked at a special spacecraft preparation center at the European spaceport in Kourou, where teams are checking it after its journey to French Guiana ahead of launch

Credit: Photo – © ESA / CNES / Arianespace (ESA Standard Licence)

- Load scale: from 1U to several tons

- The road to Kourou: express air freight or a voyage across the Atlantic

- EPCU at CSG: where payload preparation begins

- Transit Hall: unloading and the way to the airlock

- Air lock: controlled transfer between zones

- Clean room: coveralls, air shower, and… manual dust counting

- Solar arrays and onions: life between critical steps

- Satellite check-out: tests, measurements, and go/no-go decisions

- Transport between facilities: CCU and the logic of “sealed transfer”

- Hazardous operations: pyrotechnics, blast shields, and hypergolic fuels

- Mating: satellite on the adapter

- Encapsulation: the fairing as a controlled environment

- How the software can support the payload preparation?